Many of us are familiar with titanium dioxide (TiO2), a whitener commonly used in sunscreens and paints such as the white lines seen on tennis courts. Less well known are other higher titanium oxides — those with a higher number of titanium and oxygen atoms than TiO — that is now the subject of intensifying research due to their potential use in next-generation electronic devices.

Now, researchers at Tokyo Tech have reported superconductivity in two kinds of higher titanium oxides prepared in the form of ultrathin films. With a thickness of around 120 nanometers, these materials reveal properties that are only just beginning to be explored.

“We succeeded in growing thin films of Ti4O7 and γ-Ti3O5 for the first time,” says Kohei Yoshimatsu, lead author of the paper published in Scientific Reports.

Until now, the two materials had only been studied in bulk form, in which they behave as insulators — the opposite of conductors. The formation of electrically conductive thin films is therefore seen as a big advance for fundamental physics.

The researchers found that the superconducting transition temperature reached 3.0 K for Ti4O7 and 7.1 K for γ-Ti3O5. Achieving 7.1 K even in simple metal oxides is “an amazing result,” says Yoshimatsu, as “it represents one of the highest known among these oxides.”

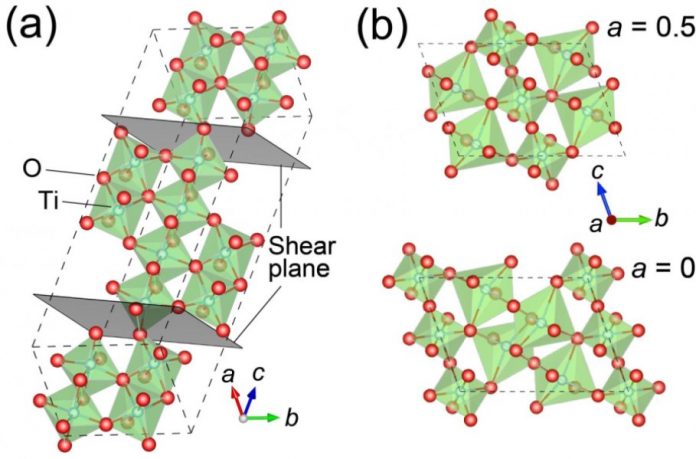

The thin films are epitaxial, meaning that they have a well-aligned crystalline structure. “They are extremely difficult to grow,” says Yoshimatsu. “In our study, instead of using conventional TiO2 as the starting material, we chose to begin with the slightly more reduced Ti2O3.” Then, under precisely controlled atmospheric conditions, the Ti4O7 and γ-Ti3O5 films were grown layer by layer on sapphire substrates in a process called pulsed-laser deposition.

To verify the crystalline structures of the films, the team collaborated with researchers at the National Institute for Materials Science (NIMS) who used characterization techniques such as X-ray diffraction (XRD) using synchrotron radiation at SPring-8, one of the world’s largest facilities of its kind situated in Hyogo Prefecture, western Japan.

As yet, no one knows exactly how superconductivity arises in these titanium oxides. The irregular (or what is known as non-stoichiometric) arrangement of oxygen atoms is thought to play an important factor. This arrangement introduces oxygen vacancies1 that are not stable in bulk form. By creating just enough conductive electrons, the oxygen vacancies may help induce superconductivity.

Yoshimatsu says that more work will be needed to examine the underlying mechanisms. As titanium oxides are cheap and relatively simple compounds made of only two kinds of elements, he adds that they are attractive for further research.

In addition, he says that the study may advance the development of Josephson junctions2 that could in future be used to build new kinds of electronic circuits and, ultimately, faster computers.