In microelectronic devices, the bandgap is a major factor determining the electrical conductivity of the underlying materials, and a more recent class of semiconductors with ultrawide bandgaps are capable of operating at much higher temperatures and powers than conventional small-bandgap silicon-based chips. Researchers now provide a detailed perspective on the properties, capabilities, current limitations and future developments for one of the most promising UWB compounds, gallium oxide.

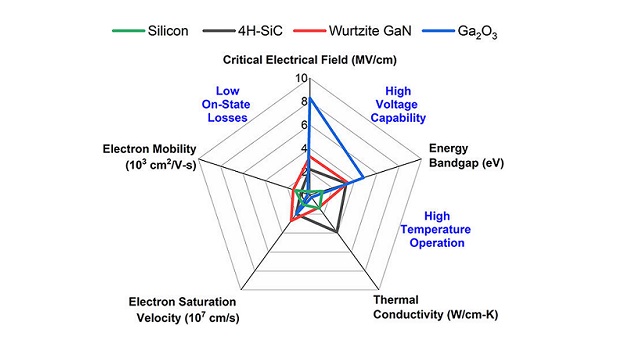

In microelectronic devices, the bandgap is a major factor determining the electrical conductivity of the underlying materials. Substances with large bandgaps are generally insulators that do not conduct electricity well, and those with smaller bandgaps are semiconductors. A more recent class of semiconductors with ultrawide bandgaps (UWB) are capable of operating at much higher temperatures and powers than conventional small-bandgap silicon-based chips made with mature bandgap materials like silicon carbide (SiC) and gallium nitride (GaN).

Researchers at the University of Florida, the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory and Korea University provide a detailed perspective on the properties, capabilities, current limitations and future developments for one of the most promising UWB compounds, gallium oxide (Ga2O3).

Gallium oxide possesses an extremely wide bandgap of 4.8 electron volts (eV) that dwarfs silicon’s 1.1 eV and exceeds the 3.3 eV exhibited by SiC and GaN. The difference gives Ga2O3 the ability to withstand a larger electric field than silicon, SiC and GaN can without breaking down. Furthermore, Ga2O3 handles the same amount of voltage over a shorter distance. This makes it invaluable for producing smaller, more efficient high-power transistors.

“Gallium oxide offers semiconductor manufacturers a highly applicable substrate for microelectronic devices,” said Stephen Pearton, professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Florida and an author on the paper. “The compound appears ideal for use in power distribution systems that charge electric cars or converters that move electricity into the power grid from alternative energy sources such as wind turbines.”

Pearton and his colleagues also looked at the potential for Ga2O3as a base for metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors, better known as MOSFETs. “Traditionally, these tiny electronic switches are made from silicon for use in laptops, smart phones and other electronics,” Pearton said. “For systems like electric car charging stations, we need MOSFETs that can operate at higher power levels than silicon-based devices and that’s where gallium oxide might be the solution.”