Every year, hundreds of millions of tons of CO2 are emitted through maritime transport, causing serious harm to the climate. As scientists around the world test new propulsion methods capable of replacing fuel oil in ships, Fraunhofer researchers are working as part of an international consortium to develop ammonia-based fuel cells. When used as fuel for ships with electric engines, ammonia is as eco-friendly as hydrogen but easier and safer to handle.

At present, hydrogen is the primary focus in the area of sustainable energy: there are plans in place to use hydrogen to fuel buses, commercial vehicles, and even cars. However, the Fraunhofer Institute for Microengineering and Microsystems IMM in Mainz is working on another promising possibility. As part of the ShipFC project, the Fraunhofer Institute is collaborating with 13 European consortium partners to develop the world’s first ammonia-based fuel cell for shipping. Fraunhofer’s researchers are responsible for developing the catalytic converter, which prevents the production of emissions that would harm the climate.

Maritime transport is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. According to information provided by the German Environment Agency (UBA), maritime transport on the world’s oceans is currently responsible for approximately 2.6 percent of global CO2 emissions. In 2015, about 932 million tons of CO2 were emitted, and that figure increases every year. Clearly, countermeasures are urgently needed.

The ShipFC project is intended to prove that the new emission-free propulsion technology works safely, reliably, and smoothly, even in large ships and on long voyages. The project is being coordinated by NCE Maritime Cleantech from Norway, an organization that aims to develop eco-friendly technologies in the maritime sector.

The advantages of ammonia

Ammonia is primarily known for its use as a fertilizer in the agricultural sector. However, it can also function as a high-quality energy carrier. Prof. Gunther Kolb, director of the energy division and deputy institute director at the IMM, explains: “Ammonia has significant advantages over hydrogen. Hydrogen has to be stored at -253 degrees Celsius as a liquid, or at pressures of around 700 bar as a gas. Liquid ammonia can be stored at a reasonable temperature of -33 degrees Celsius at standard pressure, and +20 degrees Celsius at 9 bar. That makes storing and transporting this energy carrier considerably easier and more straightforward.”

How the fuel cell and catalytic converter work

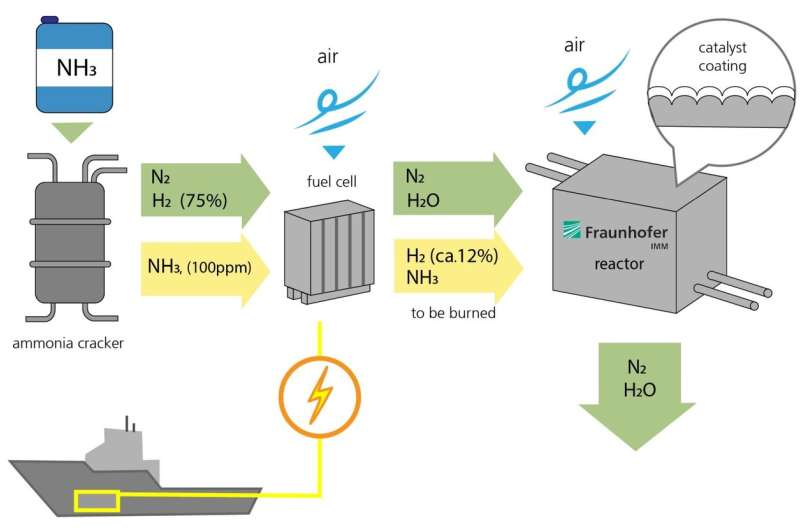

The process for generating electricity from ammonia functions in a similar way to hydrogen-based power plants. First, ammonia (NH3) is fed into a fission reactor, where it is split into nitrogen (N2) and hydrogen (H2). 75 percent of the gas consists of hydrogen. A small amount of ammonia (NH3, 100 ppm) is not converted and left over in the gas stream.

Second, nitrogen and hydrogen are fed into the fuel cell, and air is introduced, allowing the hydrogen to burn and form water. This produces electrical energy. However, the hydrogen isn’t fully converted in the fuel cell. Around 12 percent of the hydrogen and some residual ammonia leave the fuel cell uncombusted. This residue is then fed into the catalytic converter developed by Fraunhofer IMM. Here, air is introduced and the residue comes into contact with a corrugated metal foil coated with a powdered layer of catalytic particles that contain platinum. This triggers a chemical reaction. Ultimately, the only end products are water and nitrogen. An optimal reaction process will not even produce environmentally harmful nitrogen oxides.

The research team at the IMM are also developing the reactor that contains the catalyst, which functions passively. The reactor controls the temperature and the gas flow. For example, it preheats the catalyst before the engines are even started, as it is less efficient when cold. “The temperature of the gases that flow through the catalytic converter should probably be around 500 degrees Celsius for the waste gas purification process to be as efficient as possible,” explains Kolb.

Fraunhofer IMM researchers have decades of experience in developing reactors including catalysts for a wide variety of applications in the transport and mobility sector. The Mainz-based institute has nine test rigs, but purifying waste gas from ammonia fuel cells with a capacity of 2 megawatts is still a technological challenge. “We have to develop our existing ammonia-powered fuel cell technology further, and the catalytic converter for a ship is obviously much bigger than that of a normal car,” says Kolb.

Catalytic converter test rig: This is used to test all the functions of a catalytic converter, as well as its efficiency in waste gas purification. Fraunhofer IMM has a total of nine test rigs. Credit: Fraunhofer

The status of the project

The IMM team is planning to complete an initial, small prototype by the end of 2021, to be followed by an actual-size prototype by the end of 2022. In the second half of 2023, the first ship with an ammonia-powered fuel cell will put out to sea—the Viking Energy, a supply vessel owned by the Norwegian shipping company Eidesvik. After that, other types of vessels, such as cargo ships, will be equipped with ammonia-powered fuel cells.

Ammonia’s potential for the future

The ammonia is provided by YARA, a partner in the ShipFC consortium. The chemical company currently produces one third of the ammonia used worldwide. The ShipFC project uses “green” ammonia, i.e. ammonia produced from renewable energy sources.

ShipFC is opening up major opportunities for a previously undervalued energy carrier. IMM researcher Gunther Kolb elaborates: “We see ammonia not as a direct competitor to hydrogen, but rather as an additional option in the area of sustainable energy. With its storage advantages, this environmentally friendly technology for power generation certainly has a role to play. Using it in ships is just the beginning.”

Ammonia’s potential has also been recognized at a political level, with the European Union providing 10 million euros in financial support for the ShipFC project.