Deep learning is a potential tool for scientists to glean more detail from low-resolution images in microscopy, but it’s often difficult to gather enough baseline data to train computers in the process. Now, a new method developed by scientists that could make the technology more accessible—by taking high-resolution images, and artificially degrading them.

The new tool, which the researchers call a “crappifier,” could make it significantly easier for scientists to get detailed images of cells or cellular structures that have previously been difficult to observe because they require low-light conditions, such as mitochondria, which can divide when stressed by the lasers used to illuminate them. It could also help democratize microscopy, allowing scientists to capture high-resolution images even if they don’t have access to powerful microscopes.

Deep learning is a type of artificial intelligence (AI) in which computer algorithms learn and improve by studying examples. To use deep learning to improve microscope images—either by improving the resolution (sharpness) or reducing background “noise”—the system would need to be shown many examples of both high- and low-resolution images. That’s a problem because capturing perfectly identical microscopy images in two separate exposures can be difficult and expensive. It’s especially challenging when imaging living cells that might be moving around during the process.

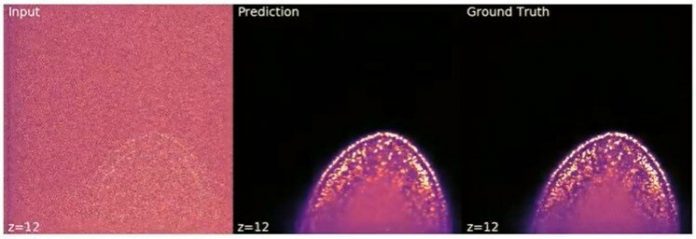

That’s where the crappifier comes in. The method takes high-quality images and computationally degrades them so that they look something like the lowest low-resolution images the team would acquire.

The team showed high-resolution images and their degraded counterparts to the deep learning software, called Point-Scanning Super-Resolution, or PSSR. After studying the degraded images, the system was able to learn how to improve images that were naturally poor quality.

That’s significant because, in the past, computer systems that learned on artificially-degraded data still struggled when presented with raw data from the real world.

They tried a bunch of different degradation methods and found one that actually works. You can train a model on your artificially-generated data, and it actually works on real-world data.

Using our method, people can benefit from this powerful, deep learning technology without investing a lot of time or resources. You can use pre-existing high-quality data, degrade it, and train a model to improve the quality of a lower-resolution image.

The team showed that PSSR works in both electron microscopy and with fluorescence live-cell images—two situations where it can be extraordinarily difficult or impossible to obtain the duplicate high- and low-resolution images needed to train AI systems. While the study demonstrated the method on images of brain tissue, Manor hopes it could be applied to other systems of the body in the future.